|

|

|||

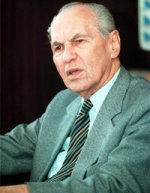

Eduard Goldstücker dead

Eduard Goldstücker dead

Czech literary scholar who was an expert on the work of Franz Kafka — and himself suffered Kafka-esque persecution under Stalinism

The Czech intellectual and diplomat Eduard Goldstücker linked in his life the extraordinarily fertile cultural world of late Habsburg and interwar Prague with the horrors that befell Czechoslovakia under Nazism and Stalinism. Active in the exiled Czechoslovak Resistance in the Second World War, a victim of 1950s Stalinist show trials back in Prague, exiled again after the crushing of the Prague Spring in 1968, he attempted in his academic work to explain the spirit of Franz Kafka and his nightmarish writings, and to relate them to his own painful experience of the 20th century’s assault on individual freedom.

Goldstücker was born a citizen of the late Habsburg empire in Podbiel in 1913, and was educated at Charles University in Prague in the mid-1930s, as the young Czechoslovak republic struggled with its ethnic divisions and Hitler’s attempt to exploit them. He came face to face with these tensions as a young man working for the League for Human Rights in Prague in the late 1930s, but in 1939, as the Germans invaded the Czech lands, he left for Britain — a place he knew already after a period studying at Oxford University.

During the Second World War he was involved in the Czechoslovak government-in-exile in London under Eduard Benes, and then became a diplomat in the postwar Czechoslovak Government, serving in London again and in Tel Aviv.

He was sufficiently sympathetic to the Communist cause to remain in office as the Communists took control in Czechoslovakia in the late 1940s. But in December 1951 Goldstücker fell victim to the purges and show trials which spread a wave of terror across Czechoslovakia and other Soviet bloc states, inspired by Stalin’s own paranoia and brutality.

Goldstücker was suddenly arrested, taken to a secret police prison near Prague, and kept for 18 months in isolation, apart from frequent interrogations. Asking why he had been arrested, he was told: “That is what you will tell us, not what we will tell you.”

He was eventually tried at the Supreme Court on charges of high treason, espionage and conspiracy to subvert the constitution, and was obliged to repeat a confession he had signed after endless questioning and intimidation. His defence lawyer, appointed by the government, began his submission by saying: “For my client the supreme punishment is being demanded, and there is no doubt that he deserves it.” But Goldstücker was not executed as he had expected, and after further imprisonment he was released in late 1955. The same Supreme Court declared now that his indictment had been illegal.

Goldstücker said later that his horrific experience had taught him that the whole system was “built on a lie”. And in explaining how such lies could assume control he drew more and more on his studies of Franz Kafka, who had foreseen with uncanny precision the tyranny of pseudo-justice administered to the helpless individual by an all-powerful authority. Goldstücker, now teaching in the faculty of German literature at Charles University, published a well-received volume on Kafka in 1964.

The previous year he had organised a conference on the same author at Liblice castle near Prague — a daring enterprise given the Communist state’s suspicion of Kafka’s writings and the hitherto tight restrictions on cultural debate. As freer debate at events like this flowed into the Prague Spring political reform movement, Goldstücker played a prominent role through the Writers Union, which he chaired from 1968-69. But as censorship and restrictions were reimposed after the crushing of political reform by Warsaw Pact invasion, Goldstücker again went into exile in Britain, and was stripped of his Czechoslovak citizenship by the authorities in 1974.

He continued his studies of Prague German-language literature as a professor at the University of Sussex in the 1970s, publishing in 1972 a study of The Czech National Revival: The Germans and the Jews. And he was surprised and delighted in his retirement to be able to return to live in Prague following the collapse of Communist rule in 1989. His return was marred, however, by the often hostile reception given by some in the new Czech political generation to those who had been prominent in the Prague Spring reform movement.

Reformers such as Goldstücker were seen as having sought to prolong Communist rule by making it more palatable, rather than sweeping it away as the “velvet revolutionaries” had done under Vaclav Havel. Goldstücker, who felt that such criticism was based on naivety about the situation in 1968, said he sometimes felt like persona non grata in the Prague of the 1990s — a familiar feeling for a man who had suffered so much from the vicissitudes of totalitarian rule in his native land. He remained a valued, highly articulate witness to what had happened to Czechoslovakia and its culture in the turbulent span of his lifetime.

He is survived by his two daughters.

Eduard Goldstücker, writer and diplomat, was born on May 30, 1913. He died on October 23 aged 87.

(From: The Times, Copyright 2000 Times Newspapers Ltd.)