|

|

|||

Roots of Kafka´s The Trial

By Gustavo Artiles

Watching once again David Hugh Jones´s 1993 film ´inspired on´ the book lead me to reread it for the umpteenth time. Per force, it also made me recall Orson Welles´ previous great version. To be fair to any film director, one must always bear in mind that it is film we are talking about, not the book itself. We are talking cinema here, images, motion, dialogue, sounds. Great books will always make mediocre films, because the literature has to be cut short or altogether eliminated, but it is also true that many mediocre books may make great films. And yet, Kafka´s pages flow like scenes and camera shots, and the words don´t seem to interfere with our sense of cinematic atmosphere. This is partly due to the author´s style, kept simple and direct, fairly descriptive and allowing any surprises to come only from the facts told. Surprises on the side of the reader, of course, more than the hero, who barely questions - in a very cold and logical manner - the to us surrealist nature of the events and their details. (In Metamorphosis, the extraordinary transformation is fairly well accepted by the victim, except for not being a very pleasant thing). I will only say that the film is beautiful, Prague is beautiful, “even the orchestra is beautiful”. But let´s now talk about the book.

One could see three elements making up the structure and the shape of this story. One is the straight story. K wakes up one morning in his pension to see three individuals, identified as court officers, who are there to arrest him, and the bring some of K´s colleagues as witnesses. This is already odd, but that´s how things seem to be in that land, so we accept it. On the other hand, that´s how things are going to continue being all the time, for the story follows a logic all of it´s own for, as Welles pointed out, this is “the logic of the dreams” (but this is not “the stuff that (most) dreams are made of”). Sticking to such logic was one of Kafka´s originalities in The trial and most of his works.

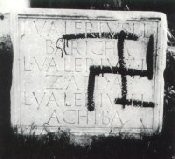

The second element is the metaphor that without exception is the one always taken up by film makers, that of the exposé of an oppressive regime. A visionary, many have said, he saw what was coming, thinking of Nazi Germany. But when Kafka died, in 1924, Nazism was merely brewing and the other notorious example of a Western State where arbitrary actions were being taken was Soviet Russia, only seven years old and more than a decade away from the worst purges. I do not think Kafka was so much a prophet as a shrewd observer of human nature, and as a lawyer, he knew how the law could be and was manipulated although, again, he was not denouncing the Austro-Hungarian empire specifically, not a particularly oppressive State and one in which he did not feel particularly oppressed either, except for his working hours, that interfered with his habit to write until very late at night. But he was a humanist concerned with humanity as a whole, regardless of nationalities and religions, and the problems he wants to present to us are important because they are universal, this one referring to the abuse of power anywhere, at any given time.

So we come to a third, crucial element which I don´t believe has been pointed out. To any who want to understand the reasons for all the surrealist, inconsistent situations thrown to us in the book, I would suggest to replace the occupations of all the judges, lawyers, court officers and their assistants by doctors, nurses and other medical staff, that is, standard medical staff, and the court and other buildings by hospital wards. Then it all will make better sense.

Conversations where they refer to someone else´s opinion on how the case is going, its possible outcome, the need to pay constant attention to it, the frequent consultations, even the end itself, are describing the feelings of a man from the very first time he is told he is suffering from a possibly fatal illness. This is invariably sudden and unexpected in real life too. Then come the questions on what the best course of action may be, the opinion of your doctor and possibly other doctors as well. Equally medical are the descriptions of the three possible forms of acquittal that Tintorelli the painter describes to him: total, ostensible and indefinite. Aren´t these the three possible results of the diagnostic of a potentially fatal illness? You could be cured instantly, perhaps by some surgical means, or temporarily relieved until some day the symptoms recur, or destined to live with your illness for the rest of your days. The case is not a legal case at all, it is a medical case.

Kafka was obsessive about health, and he had a reason to be: the Damocles sword of TB pended over him since very early, and he died prematurely from it. He was also an extreme vegetarian, never touched alcohol and was fanatical about exercise, to the extreme of systematically practicing callisthenics shirtless in front of his open window during winter. All this is well documented in his various biographies. So, with this knowledge, the thesis I am presenting here cannot be dismissed.

It is true that reading the novel with this knowledge in mind may make it less magical and mysterious. And making a film under that light might trivialise the story. But that was the mastery of Kafka´s, keeping the secret to himself and taking advantage of the account of K´s ordeal (which is his medical ordeal) to expose his despise for political corrupt regimes, with corrupt officials and corrupt lawyers. For he knew very well that even honest, idealistic governments will have corrupt elements inside them, and that´s what needs to be exposed and fought, for they both are and probably always will be opposite sides of all human societies.