|

|

|||

Ragged Bits of Meaning, Wound on a Star-Shaped Spool for Thread

by Anya Meksin

(The Cares of a Family Man)

«Some say the word Odradek is of Slavonic origin, and try to account for it on that basis. Others again believe it to be of German origin, only influenced by Slavonic. The uncertainty of both interpretations allows one to assume with justice that neither is accurate, especially as neither of them provides an intelligent meaning of the word.

No one, of course, would occupy himself with such studies if there were not a creature called Odradek. At first glance it looks like a flat star-shaped spool for thread, and indeed it does seem to have thread wound upon it; to be sure, they are only old, broken-off bits of thread, knotted and tangled together, of the most varied sorts and colors. But it is not only a spool, for a small wooden crossbar sticks out of the middle of the star, and another small rod is joined to that at a right angle. By means of this latter rod on one side and one of the points of the star on the other, the whole thing can stand upright as if on two legs.

One is tempted to believe that the creature once had some sort of intelligible shape and is now only a broken-down remnant. Yet this does not seem to be the case; at least there is no sign of it; nowhere is there an unfinished or unbroken surface to suggest anything of the kind; the whole thing looks senseless enough, but in its own way perfectly finished. In any case, closer scrutiny is impossible, since Odradek is extraordinarily nimble and can never be laid hold of.

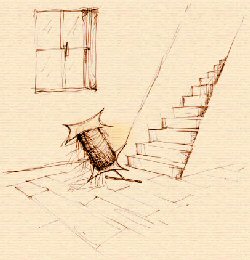

He lurks by turns in the garret, the stairway, the lobbies, the entrance hall. Often for months on end he is not to be seen; then he has presumably moved into other houses; but he always comes faithfully back to our house again. Many a time when you go out of the door and he happens just to be leaning directly beneath you against the banisters you feel inclined to speak to him. Of course, you put no difficult questions to him, you treat him--he is so diminutive that you cannot help it--rather like a child. "Well, what's your name?" you ask him. "Odradek," he says. "And where do you live?" "No fixed abode," he says and laughs; but it is only the kind of laughter that has no lungs behind it. It sounds rather like the rustling of fallen leaves. And that is usually the end of the conversation. Even these anwers are not always forthcoming; often he stays mute for a long time, as wooden as his appearance.

I ask myself, to no purpose, what is likely to happen to him? Can he possibly die? Anything that dies has had some kind of aim in life, some kind of activity, which has worn out; but that does not apply to Odradek. Am I to suppose, then, that he will always be rolling down the stairs, with ends of thread trailing after him, right before the feet of my children, and my children's children? He does no harm to anyone that one can see; but the idea that he is likely to survive me I find almost painful».

-----------------------------------------------------------

To attempt an interpretation of “The Cares of a Family Man” is to become the Family Man himself, to enter his baffled persona and to face his inexplicable dilemma. The story is the reader’s Odradek, confronting you amid the complacency of your intellectual home, and then remaining incomprehensible despite all your efforts. Just as Odradek, at first glance, resembles a common household object, so too Kafka’s story initially appears to conform to certain familiar literary shapes. The reader skims the “diminutive” text, encounters Odradek, assumes the tale is allegorical, and begins to reread in order to find the right fit: what does Odradek stand for? what does he represent? But the story stubbornly resists an adequate correlation between Odradek and any existing entities or concepts in our world. It is as if the little text has somehow transcended the very system in which symbolism is possible, just as Odradek has somehow transcended the logic of the physical world. Odradek is a metaphysical rupture in the reality of the family man, and the story is an epistemological rupture in the reality of the reader. The need to normalize this rupture constitutes the “cares” or “worries” of the family man—a series of circular musings on the origin and destiny of Odradek, an effort to integrate him into the domestic regularity that it is the family man’s duty to preserve. For the reader, these same efforts at normalization give rise to a series of equally circular and anxious interpretations of the text, all proving inconclusive, but each fueling the need for the next.

Kafka, always prophetic, alludes to this interpretive anxiety in the first few sentences of the story, where he rather cruelly parodies future scholarly efforts at understanding his own completely enigmatic work:

“Some say the word Odradek is of Slavonic origin, and try to account for it on that basis. Others again, believe it to be of German origin, only influenced by Slavonic. The uncertainty of both interpretations allows one to assume with justice that neither is accurate, especially as neither of them provides an intelligent meaning of the word” (427-8)[i].

It is here that Kafka unmistakably links the family man’s attempts to “unravel” the mystery of Odradek to a wider interpretive dilemma, and here too that he preemptively dismisses all efforts at interpretation as futile. It is tempting, based on this first paragraph, to view “The Cares of the Family Man” as simply a user’s manual for reading Kafka himself, where Odradek is a living figure of the text, an embodiment of the literary act Kafka performed. The parallels are enticing: Kafka’s work too, seems incomplete, somehow ragged and senseless, “but in its own way perfectly finished”; and Kafka’s humor can perhaps be seen as lungless, “like the rustling of fallen leaves,” in that it is a sinister amusement at the proof that it is impossible to live, exercised by one who is nevertheless making the attempt. But even though this element of self-reference is indisputably present within the text, to limit readings of the story to this narcissistic concern of the writer with his own work is to ignore the massive scope that Odradek’s little parable offers.

There is something undeniably epic, cosmic, vast about Odradek’s frail and humble presence. He is so small and childlike, but somehow overwhelmingly significant, like he carries with him some enormous truth, hiding in the shadow behind his thin wooden frame. He is like a diplomat from a realm humans did not know existed, and his being is an indexical sign, a fingerprint of that realm. Since we are accustomed to juxtaposing the human sphere with the divine, or the natural with the preternatural, it becomes tempting to decide that Odradek is a messenger from a transcendent realm, sent here to pierce the surface of our mundane reality and to remind us, through his existence, of the God we have forgotten. Odradek, then, is a prophet, a living crucifixion—and his physical description does not discount such an interpretation: “a small wooden crossbar sticks out of the middle of the star, and another small rod is joined to that at a right angle” (428). His emergence in the now dehumanized human sphere is a reprimand, a symptom of the cosmic order having broken asunder. In a safe and sane universe, Odradek would never haven been allowed to appear and frighten the family man, but because the human and the super-human have lost their orderly relation, they now interpenetrate in an act of collision.

It’s easy to spiral off in an interpretive frenzy, having been thrown a bone by the expansive possibilities of the text. But when you read back through to see if the rest matches up, you find that Odradek’s “sphere,” or the tone of his character in the story, is completely devoid of spirituality and transcendence. In fact, Kafka clearly emphasizes Odradek’s physical qualities, likening him to, if anything, the mundane world itself, populated by practical, lifeless objects. At the opposite extreme from the theological approach, a Marxist reading immediately rears its head: Odradek is that which man himself has created. He represents the world of manmade practical objects (thread for mending), but in a form completely separated from the human work that produced them. The family man’s tense relationship with Odradek is the embodiment of the capitalist worker’s alienation from production. The worry that Odradek elicits illustrates the degree to which “things” have come to dominate human life, imperiously demanding attention, maintenance, service. The family man is Poseidon, given the oceans to rule, but actually forced into a submission to his possessions by the incessant administration they require. And not only do “things” dominate life by demanding constant attention, they also serve as a reminder of death in the fact that they will outlive man, to be inherited by his children. “Things” are meant to improve life, to further animate it, but instead they remain dead, mute, wooden, incapable of absorbing the meaning that humans seek to bestow upon them.

This disjunction between a lifeless physical reality and the deluded expectations humans have of that reality points to a larger context in which the figure of Odradek once again finds a central location. This time, Odradek stands for the entire physical world, not just manmade objects, but all of nature, which human beings incessantly probe for hidden, transcendent mystery, for some locked up higher truth, accessible to the human soul. But the physical world, like Odradek, is relentlessly cold and menacing—essentially, meaningless. There is a terrible incongruity between our yearning, grasping consciousness, and the impenetrable, eternal reality of the dead universe. In fact, the accident of our thinking, knowing minds in this barren world of objective physicality is just as improbable and shocking as Odradek’s appearance in the family man’s dwelling. In both cases, normality is undermined by an aberration that “does no harm to anyone that one can see,” but that nevertheless represents a rupture of the greatest magnitude.

No matter how hard we try to integrate all empirical data into one coherent, knowable, classifiable system, we still come up against the limit of our consciousness, the limit of what we can know and understand about the lot that has been given us. Odradek stands at that very edge of knowability—he really is the doorkeeper (by no coincidence frequenting “entrance halls”), silently holding a “keep out” sign, and yet stirring the imagination, and whetting man’s appetite for the forbidden by his very appearance.

It is not of a forgotten God that Odradek reminds us, but of the cold and brutal void that our notion of God masks. The text seems to rally behind this interpretation. The word Odradek is beyond language symbols, although it appears to have its origins in known human languages, tempting the story’s etymologists, yet yielding no answers. For the reader, however, ignoring Kafka’s advice to give up on the meaning of the word yields a further clue: “Odradek” is, in fact, slightly intelligible from the Slavonic point of view, where there exists an antiquated verb, “odradeti,” which means “to counsel against”. Odradek, then, is the little naysayer, the silent dissuader. And specifically, he seems to advise against interpretation itself, against attempts at meaning-making. His presence is a cold announcement of existential fact: “I mean nothing, but here I am.” (Let’s all repeat that to ourselves every morning!) And Odradek’s physical description, like his name, at first appears to belong to a familiar human world. But the description is a riddle: just as the word can never be fully understood, so too Odradek can never be visualized. The meticulous realism is sarcastic and cruel, because the vivid details do not add up to a complete composite sketch. Again, we come up against the empirical limits of our powers of comprehension. His resemblance to meaningful things is arbitrary: he is not a derivative of our conscious world, but a coincidentally similar, yet wholly unrelated occurrence.

No wonder he is such a worry to the family man, who is trying earnestly to “keep house,” or to retain a handle on this earthly existence. Odradek is deathless, and as such, is in some way off-limits for those who die. But the intermediate sphere Odradek occupies—that between thing and conscious being—seems to offer a strange possibility of freedom that the family man himself cannot have. Odradek cannot be caught, he is nimble, and has no fixed abode—he cannot be constrained by any classifying system of thought. But this freedom is only possible through the surrender of life, of breathing, and of every volitional intention that has a definite goal. To be free, one cannot have an “aim in life”. Odradek, this “real” being that leaps about freely and immortally is made up of elements of ordinary everyday things and human languages. These elements have the character of remnants, and yet the whole shows no signs of ever being anything more complete than what it is now. What does this mean? When people and things are no longer governed by goals and purposeful volitional impulses, when they are rejected as useless junk, swept aside like fallen leaves, it is then that they become free, whole, “saved”. Old age and childhood here merge, since both are “useless,” and thus outside the clutches of existence.

The act of trying to interpret Odradek’s story is that of trying to solve a riddle, of the form “what is wooden and star-shaped and has no fixed abode, etc.” Just like visualizing Odradek requires attempting to coalesce a number of contradictory details into one composite figure, so too interpreting the story requires attempting to coalesce a number of enigmatic sentences into one composite meaning for the story, or meaning for Odradek. The story of Odradek, like the figure itself, is a paradox: to realize that Odradek stands as an antithesis to meaning/interpretation is to have already infused him with meaning, to have interpreted him. Once this final interpretation is apparent, the text should just combust in your hands. But it doesn’t, and the discourse continues. Just like once we face the void at the center of consciousness, once the family man discovers an Odradek in his house, there are only two options: immediate suicide, or continuing along as best we can, given the circumstances. For some reason, most of us choose the latter.

[i] Kafka, Franz (1971). The Complete Stories. Schocken Books: New York.

Anya Meksin is a recent graduate of Yale University, where she studied literature, film, and art. She currently lives in Chicago, Illinois, and works in video and photography. Her recent video, "The Argument," is available for viewing at

http://www.meksin.com/projects.html